From British and Irish Drama 1890-1950: A Critical History

by Richard

Farr Dietrich

Link to

Title Page & Table of Contents for Entire Book

COMMON

CAUSE: A NATIONAL THEATER

The

modern era is known for its intense and often bloody conflict—world wars, hot

and cold, revolutions and counterrevolutions, civil wars, religious wars, class

struggle, strife of every kind. It’s

unlikely that a more contentious age has ever been known in terms of the number

of casualties. The conflict over

theories of dramatic art that this study has recorded is therefore perfectly in

step with the times, though of course such intellectual warfare seems mild in

context. The debate may seem much ado

about nothing to us now, but it was probably necessary to clarify matters and

raise consciousness. If it is true that

a high drama is central to culture and necessary to its well-being, then

Archer, Shaw, and the other avant-garde critics were right in taking an

antagonistic stance toward the decadent, fallen drama of Victorian

England. Ironically, the sense of having

to do battle in order to get a hearing in the theater ultimately served the

foes as well as the friends of realism.

But this was all to the good in that the outcome of waging critical war

was to foster the best of each kind of New Drama, realistic or

nonrealistic. If the warfare has quieted

down because we’ve discovered that all New Drama has roots in Old Drama and

that all kinds of drama are necessary to a complete account of reality, we

should nevertheless be thankful for the spark that this debate gave to the creation

of a high drama.

A

high drama was indeed the accomplishment of the modern period. In sixty years the drama had been lifted from

its nineteenth-century slough of mediocrity; playwrights, protected by

copyrights from 1891 on,

published their plays as soon as they could, expecting them to be judged as

literature; and ways had been found to make the theater and the drama work to

their mutual benefit, rather than theatricalism

dominating the play. By 1950 such a considerable body of

worthwhile drama had been produced as to make it obvious that “Britain” (a name

replaced midway by the division into Ireland and the United Kingdom) had once

again reached the front rank of those with a nationally significant drama. Shakespeare was no longer overburdened. Yet the problem of supporting such a high

drama grew more acute as expenses rose.

Whatever the differences of opinion in other

areas, most of the leading figures of modern drama and theater agreed on the need

for a subsidized national theater, in both the UK and Ireland. The increasing commercialization of the

theater was driving out those few remaining elements of artistic integrity that

gave the theater whatever cultural stature it possessed. Long runs favored shallow, escapist “hits,”

often musicals, at the expense of the enlarging repertoire of straight drama. The only solution was the revival of a

repertory system, but no West End theater or

commercial theater in Dublin could afford for long to drop the long run and

gamble on a repertory. An endowed

theater was obviously needed, in both Dublin and London

Calls for an endowed national theater in

England, at first mainly to honor Shakespeare, can be traced back to at least

the mid-nineteenth century, but the 1870s saw the first pleas (led by Tom

Taylor and J. R. Planché) for a theater that would

subsidize a modern repertory as well.1 A young William

Archer took up the cause in 1877; he was further inspired by an 1879 visit to London by France’s subsidized

Comédie Française, and by

the 1890s he became its principal advocate, though Henry Arthur Jones had been

with him from about the mid-eighties. As the years rolled on, more and more

voices were added to the clamor for a national theater, particularly those of

the many amateur and semi-professional theater groups that sprang up in the

nineties and later. In 1904 Archer,

assisted by Granville Barker, wrote a very specific proposal for a national

theater (published in 1907), full

of fascinating details about the exact method of establishing such a theater

and the probable cost of every step; they looked more to private philanthropy

than to Parliament for the means.2

The struggle for a national theater in

Ireland was in some respects well ahead of the English endeavor, thanks to the

efforts of Yeats and Lady Gregory detailed in Chapter 4, and the establishment

of the Abbey Theater in Dublin as de

facto national theater, whatever its setbacks and delays along the way,

must have stood has some sort of reproach to the laggard English.

As for the English cause, though Shaw had

a hand in several of the early theater groups and as a drama critic contributed

to the national-theater agitation, he was not able to lend much prestige to the

cause until the Edwardian age, after which he kept up a fairly constant

promotion, even writing The Dark

Lady of the Sonnets (1910) to

support a Shakespeare memorial theater, eventually presiding at a ceremonial

blessing of a location in South Kensington that ultimately would not be the

site of the theater. He would have been

astonished to see the present National Theatre rise across the Thames near

The

idea of a national theater in England, though sometimes restricted to a

Shakespeare memorial, had been kept alive by many people, only a few of which

can be mentioned here. Lilian Baylis’s

management of the Old Vic between 1914 and 1923, providing a complete

repertoire of Shakespeare’s plays, is sometimes cited as “the seed from which

the present national theatre, as well as the national opera and ballet

companies, was to grow.”3 But Granville Barker’s experiment with

short-run productions at the Royal Court from 1904 to 1907 was an even earlier

seeding, as was the Edwardian efforts of the Stage Society (formed in 1899) and

Archer’s behind-the-scenes partnership with Elizabeth Robins in the New Century

Theatre effort of the nineties. Even

earlier was J. T. Grein’s Independent Theatre

(1891-98), modeled after Antoine’s Théatre Libre in

The

Taj Mahal is a temple, of

course, and that leads to the final point of this study, to underline what has

been implied all along. The marvel of this period is that a drama deemed so

trivial and insignificant in the 1880s could rise to a level that would make it

worthy of such an edifice. In an

extremely secular age, drama miraculously returned to, or at least reconnected

with, its distant source in Greek religion as life-worship. The morbidity of the convention- bound

Victorian age, led by a queen who mourned excessively for nearly half a century

the death of her prince consort, was perhaps the most explicit cause of the

need for this religious revival, but it also served well a twentieth century

that was bent on the slaughter of millions.

And in the nuclear age, potentially far more destructive, we have even

more need of it. It was precisely this

return to the religious origin of drama that made it possible for the theater

once again to gain the respect of the sort of people who build temples in order

to center their culture in high-minded aspirations and life-affirming values.

In

The Foundations of a National Drama

(1913), Henry Arthur Jones

had said that “there is no reason in the nature of things why the drama should

not again become something of a religious ceremony.”4 The playwright who took that most seriously

and perhaps thereby struck closer to the heart of drama than any other British

playwright of his time was Shaw, who summed up his years as a drama critic

thus:

Weariness

of the theatre is the prevailing note of

If one knows that Shavian call for actors to

be priests, dramatists to be apostles, and theaters to be temples of the Ascent

of Man, it is difficult to look at that modernistic Taj

Mahal of London’s National Theatre without an eerie

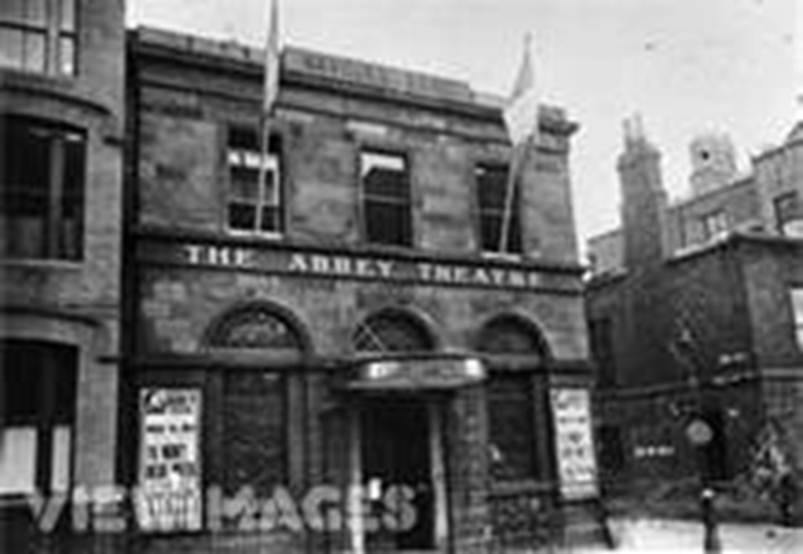

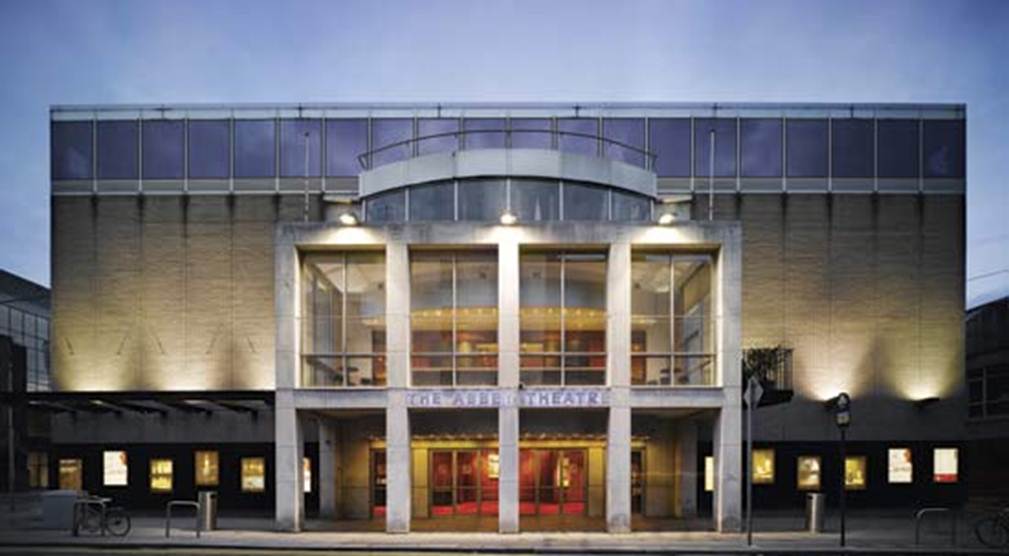

sense that, incredibly, some sort of wild prophecy has been fulfilled. Granted that the Abbey Theatre in Dublin

hasn’t looked much like a Taj Mahal,

in either of its two principal manifestations, but there, characteristically,

this temple to the Ascent of Man has resided more in the spirit of the endeavor

than in the actual building, and who’s to say which has been and will be more

effective.

Link to Title Page

& Table of Contents for Entire Book

Link

to Notes and Bibliography