From British

and Irish Drama 1890 to 1950: A Critical History

by Richard Farr Dietrich

Link to Title Page & Table of

Contents for Entire Book

End of Chapter 1

Link to Chapter 2

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION:

A RENAISSANCE OF THE DRAMA

There is a deep-lying struggle in the whole fabric of society:

a bounding grinding

collision of the New with the Old.

—Thomas Carlyle

3. The Well-Made

Play and the Problem Play

6. Figures 1-7

THE NEW DRAMA

|

There have been two

periods of great drama in British history, the first in “the Renaissance,”

Shakespeare’s age, and the second, confusingly called “the Renaissance of the

British Drama,” featuring George Bernard Shaw and the New Drama.1

It

is this renaissance of the modern period, roughly occupying the years 1890 to 1950, that is the subject of

this book.

William

Archer (1856-1924), the most influential drama

critic of the New Drama movement and translator of Ibsen, thought of the ages between

the Puritans’ closing of the theaters in 1642 and the creation

of the New Drama in the 1890s as the dark ages of the drama, with only a few

glimmerings of light along the way—Congreve, Wycherly,

Goldsmith, Sheridan, Robertson—to give hope for the future. Throughout The

Old Drama and the New (1923),

Archer used metaphors of light and dark or wasteland metaphors to contrast the

New Drama with the Old (“the whole century from about 1720 to 1820 was a dreary

desert broken by a single oasis—the comedies of Goldsmith and Sheridan”),

metaphors he applies to most of nineteenth-century drama for its

pleasure-seeking addiction to melodrama, low comedy, and other escapist fare.2

To read the diatribes

against the nineteenth-century theater by certain critics and dramatists of the

1890s is to be reminded that nothing really changes in popular culture. The

most debased of our own film and TV fare is a lineal descendant of

nineteenth-century popular theater, except that the ante on thrills and “laffs” has been considerably upped, making the Victorian

plays complained about by Archer seem tasteful and thoughtful. Yet there’s no

doubt that this escapist, often simplistically moralizing drama of the

nineteenth-century popular theater was of a decided mediocrity, not only

because it catered to the low tastes of a very undereducated and rather uncouth

audience but because it was virtually without literary value. This can partly

be attributed to the fact that without copyright laws protecting them

playwrights had gotten out of the habit of publishing their plays (except as

prompt books) and thus of thinking of them as literature, subject to criticism.

Archer’s insistence on literary quality had much to do with the return of

substance to British drama, as well as a return of improved technique. Perhaps

the most significant feature of this period is that in it the literary drama

overtook the old Theatrical Theater, making necessary a critical approach

fundamentally literary.

But

Archer’s partisan condemnation of nineteenth-century drama must be qualified in

several ways. First, though the nineteenth century was largely a desert

for the drama, it was the scene of a theatrical harvest, during which the

theater as an institution grew and flourished in the hands of great actors and

actor-managers, and all the arts and crafts of the theater were refined.

Second, though the drama of the times was mostly mediocre as literature, much

of it was first-rate as theater,

causing Britain’s growing middle class to flock to it for amusement, thus

sparking its physical and institutional development—around fifty theaters were

built in London alone between 18oo and 1890. It’s true that those seeking

greatness in the nineteenth-century theater found it mostly in the acting and

staging, and in revivals of Shakespeare and other classics, not in the

contemporary drama; but at least they found it. And those primarily seeking

entertainment were seldom disappointed. The thousand or so playwrights who

wrote between Shakespeare and Shaw, though now mostly forgotten, could at least

be generally counted on to amuse the populace according to the tastes of the

times, and occasionally even to elevate those tastes slightly. Another

consideration is that the theatricalism, abstraction,

and musical nature of much nineteenth-century drama has

been partially vindicated by the dramatic practices of twentieth-century drama,

though of course the difference is that the best twentieth-century drama made

these properties or qualities serve higher purposes. These qualifications

aside, Archer’s characterization of over two centuries of theater as desert or dark age had much validity, considering the standard set by

Shakespeare, and interested Victorians agreed that a dramatic revival was in

order. The alternative was to follow Matthew Arnold’s example in abandoning the

theater out of disgust.

But

which exactly needed to be revived—the drama or society? The word renaissance

connotes the rebirth of a people and thus might be thought too

strong a term if applied only to the drama. Most Victorians did not think of

their age as especially benighted, at least nothing a

little reform and technological and business progress couldn’t take care

of. It may have been a dark age of the drama, but in the novel and poetry

and the other arts, and certainly in the sciences and in business and industry,

most Victorians considered theirs a progressive, enlightened age. So it was

hard to convince an otherwise forward-looking people—industrializers of a world

empire and avid users of railroads, telegraphy, electricity, photography, and

telephones—that they were backward in much else besides this very specialized

and seemingly unimportant area known as the drama.

But

George Bernard Shaw, this era’s chief playwright, argued and demonstrated that,

technological progress notwithstanding, backwardness was so deeply entrenched

in the moral, religious, and governmental systems of the day that it was not

too much to call the entire age a dark age and to play its “progressiveness” as

an ironic joke. For Shaw, as well as Archer and many others, the word renaissance

was not too ambitious for the extreme measures that were needed to breathe

new life into a morally rotten society, and the drama, with its ancient roots

in the life-worshipping Greek religion of Dionysius, was precisely the means

needed. As an institution for the gathering of people together to commune on

the issues of social health and spiritual well-being, and to plumb the

mysteries of human identity in a riddling universe, employing thereby all the

arts and crafts in a unifying effort, the drama was ideally designed to be the

focus of culture, as it had been at its beginnings in ancient Greece. In fact,

the health of a nation could be determined by how central it made its drama and

how seriously it took it. For Shaw and Archer, a major diagnostic of Victorian

society was its trivialization of the theater. Only in a dark age would the

spiritual light that may illuminate the stage be allowed so nearly to go out.

A

renaissance is a period of enlightenment. The original Renaissance was awakened

to the long-lost past of the Greeks and Romans—its chief reality was that of

ancient truth rediscovered, as, for example, the way Aristotelian principles

were henceforth applied to drama. In contrast, the modern age, guided by

science to be irreverent toward the past and skeptical of received truth (as

the maverick Galileo had been skeptical of Aristotle), thought of itself as

more concerned with present reality, especially awakening

to physical reality, since it could be empirically verified. It supposed that

the physical world was scientifically knowable and controllable, and that

therefore the future could be commanded through the invention of new

technologies and new methods. From about the middle of the nineteenth century

there was a gathering insistence that art follow science in a more “realistic”

investigation of the physical world, thereby joining the March of Progress. And

so the novel followed painting, to mention two of the arts, in becoming more

“realistic” and thus supposedly less escapist. By the 1890s the New Drama as

well was identified with “realism,” with British experiments in “realism,”

however timid, as early as the 1860s (T. W. Robertson). On the continent, Émile Zola had argued in 1873 that playwrights should be

scientists too, “realistically” and tough-mindedly examining in the laboratory

of the stage the physical operation of human society and human consciousness.

And, from the seventies on, Henrik Ibsen, with his

microscopic dissection of modern Norwegian society and individual personality,

had shown how best to do it in a dramatic form. For Archer, Ibsen was the model

for the future.

But

the “realism” of an art based on illusion, as is drama, was immediately

challenged, even by some of those playwrights labeled as “realists”—Ibsen

himself fused “realism” with symbolism and flirted with expressionism. Many

artists argued that the use of “nonrealistic” modes of expression did not

necessarily mean that art was escapist; rather, art’s approach to reality could

only be through illusion

(i.e., spiritual reality)—a play, for example, was a “playing” with reality.

And the substitution of electric lights for gas lights in the eighties and

nineties, made possible by science’s regard for physical reality, did not

necessarily add to the stage’s spiritual illumination but actually seemed at

times to obscure its presentation of spiritual reality. A sign of the times,

however, was that the aggressively positivistic science of the day made people

feel apologetic about using a word like spiritual, though some playwrights

were less intimidated than others. And thus began a very complicated debate on

the nature of dramatic reality.

|

REALISM AND THE REACTION

|

“Realism”

as a dramatic style refers to the appearance of lifelikeness (verisimilitude)

in setting, costume, dialogue, gesture, facial expression, and so on. A realistic

play was to be a photographic copy of common, observable experience (in

practice, usually middle-class domestic experience, to accord with the reality

of the rise of the bourgeoisie). The stage was to appear, not as a stage, but

as a room or any actual environment; props were to be seen, not as props, but

as authentic parts of a particular everyday environment. All the developing

technology of the modern theater—hydraulic machinery, cycloramas, lighting

boards, etc.-—was brought to bear in creating the illusion of authentic

environment. A proscenium arch separated the stage from the auditorium and

framed the action taking place on the stage in a three-sided box set. Some

theaters (such as London’s Haymarket under the Bancrofts—see below)

eliminated the apron stage in front of the proscenium altogether and bordered

the proscenium so that the effect was that of looking at a framed picture. The

proscenium’s “fourth wall,” through which the audience peered, as Peeping Toms

might look into bedroom windows, was invisible by convention.

As

for the “realistic” play, no authorial intrusion was allowed, and neither

audience nor actors were acknowledged for what they were. The idea was to

achieve the illusion of re-created life, in its immediacy and dense actuality.

At its best (Ibsen and Chekhov) it did indeed give the feeling that one was

peering through an open window into someone’s house and, unobserved,

overhearing private conversation. “Realism” at its best was very persuasive in

making audiences believe that the illusion they were seeing was not an

illusion. But of course that simply made

“realism” the most outrageous of all of the theater’s pretenses—one had to

make-believe that one was not in a theater and not

looking at actors acting on a stage. But it must have been a relief to

those tired of plays that pointed the moral, and owing to its relative

subtlety, riveting to those wishing to know what it all meant. The supposed

neutrality or scientific objectivity of the author, the indirectness of the

characterization, and the relative inconclusiveness of the action forced the

viewer to pay close attention to the details in order to form judgments, with

much of the meaning of such plays occurring in the subtext and accumulating

gradually, almost imperceptibly, detail by detail.

“Realism” at first was

associated with “social drama,” for its immediate goal was to display

accurately and authentically the social environment and behavior of the

day. But this association gave realism a reputation for being

superficial, for getting lost in relatively unimportant surface detail at the

expense of portraying the more important soul of things. That was why Ibsen

resisted “realism” for so long, preferring to go on writing obsolete heroic

drama, often in verse, rather than stoop to “mere photography.” But then

it dawned on this genius that the surface of life could be used in a poetic,

symbolic way, just as great photographers were learning that the camera need

not just copy life’s exterior but could interpret and poetically evoke the

hidden depths as well. Ibsen converted to “realism” when he found that he

could use the surface to suggest the deeps and so invented what came to be

called “psychological realism,” in which the picturing of society is employed

to suggest the underlying soul or psyche. And insofar as his plays penetrated

mundane appearances, reaching to the significance of things, they were examples

of “philosophical realism” as well, and of “critical realism” insofar as they

saw through the humbug of the day. It was a neat trick, this elevating of what

seemed a trivial and mundane art into a high art, but so many missed the trick

that Ibsen was often erroneously dismissed as a mere social realist, thus

leading other dramatists to become overtly “nonrealistic” in their expression

of the psychological deeps and intellectual heights in order to separate

themselves from what was thought a second-rate art.

The

point to be underscored is that as human reality is multidimensional, the word realism

should not have been limited to the imitation of our most superficial

reality. This early mistake in terminology plagues us like an original sin,

accounting for the quotation marks around “realism” and “nonrealism”

to this point, to signify that the standard notions of these terms have created

a false distinction, for “nonrealistic” plays are no less capable of showing us

reality than are “realistic” plays, and in fact the reality conveyed by

“nonrealistic” plays may be more significant. Theater departments often wisely

use the alternate terms representational and presentational, but English

departments, caught in the toils of literary history, seem to be stuck with the

confusing “realism” and “nonrealism.” Having acknowledged

the confusion, however, we may henceforth drop the annoying quotation marks if

we keep constantly in mind that “realism” and “nonrealism”

are misnomers.

Another,

related confusion in terminology might just as well be mentioned here—that over

the term naturalism, which is used in at least three different

ways. Naturalism may refer to nothing

more than the natural-looking or natural-sounding quality of a play.

Chekhov’s plays are often cited as naturalistic in this sense, as his characters

create the impression that they are as disorganized, spontaneous, and

inarticulate as life outside of art frequently is. Shaw’s plays are not

naturalistic in this sense, for his characters are articulate well beyond

what is considered natural. In acting, Gerald du Maurier

is particularly credited with developing the most naturalistic style, which

consisted mainly of giving the appearance of not acting, a style Shaw had

little use for. This sort of naturalism, as a kind of hyperrealism, is just as

often referred to as realism pure and simple, the critics being hopelessly

inconsistent.

Naturalism (sometimes

capitalized in this sense) may also refer to a particular philosophy of life

and/or to a particular literary-dramatic embodiment of that philosophy.

Naturalism as a philosophy refers to the Social Darwinist idea that human

beings are purely the product of heredity and environment, utterly determined

in their behavior by these shaping factors of the natural world. This

philosophy may be embodied in any kind of play, realistic or

nonrealistic; and a play may have characters in it who express a naturalistic

view without the play itself being totally, or at all, supportive of naturalism

as a philosophy. Literary naturalism refers to works that attempt to embody a

naturalistic philosophy in a very specific form, in which realistically

portrayed characters are obviously and entirely at the mercy of environment and

heredity. Typically, plays of this type (

The

reactions against realism and naturalism were various, some nonrealistic

dramatic forms given names from the past, such as fantasia, burlesque,

allegory, and extravaganza, some having names invented for them, such as

symbolism and expressionism, and some seeming to fit no particular

category (most of Shaw’s plays). Of the new forms, symbolism and

expressionism most typified the modernist reaction against realism and

naturalism, having in common that they were evocations or assertions of a

reality beyond the ken of positivistic science. Symbolism pointed to a

spiritual reality behind appearances, and expressionism projected outward an

internal reality positivism overlooked.

Uncapitalized, symbolism merely refers to the use

of some things to represent other things, as a single chair on a stage might

represent all furniture, a tree might represent life, or a setting sun might

represent the coming of death. Symbolism capitalized refers to

the specific use of symbolism, conceived by a late nineteenth- and early

twentieth-century literary movement (beginning with such poets as Mallarmé, Verlaine, and Valéry, and finding its purest

dramatic expression in the plays of Maeterlinck and Yeats), to evoke a

spiritual world beyond the five senses through an associational technique that

connects things in the material world with their correspondences in the

spiritual world. Symbolism in this sense employs symbols in the least

definite of ways to suggest unseen powers and emotional realities, to evoke the

“esoteric affinities” of the writer. Symbolism was private and subjective

in that the author’s system of association, the particular way he evoked the

archetypes, was his own; but Symbolism overcame the implied chaos of

subjectivism because the correspondences activated universal archetypes, buried

in the psyche of everyone, that, when properly evoked, were capable of

connecting individuals in a collective awareness.

Expressionism

was usually a more extreme assertion of private, subjective reality, of the

sort posited by psychoanalysis, though it too might appeal to universal

archetypes. Prototypical were Strindberg’s A Dream Play and The

Ghost Sonata, peopled by bizarre, rather abstract characters

involved in dreamlike action, the logic of which was emotional and

associational rather than rational. Expressionism flowered in the

Realism

of the extreme purity Archer wanted is an aberration in the theater, for the

long tradition of the theater, before and after that brief period of the

realistic movement, has been more nonrealistic than realistic, though many of

the greatest dramatists seemed to derive strength from an alloy of the

two. From the Greeks to the New Drama, the stage traditionally presented

reality through the device of acknowledged illusion; anything

else seemed deceitful. And although the movement in nineteenth-century drama

was generally from a nonrealistic, or presentational, mode to a realistic, or

representational, mode, the movement in twentieth-century drama to the present

has been from a realistic mode not so much back to a nonrealistic mode as to a

latitudinarian attitude that anything is possible in the theater and that the

playwright is free to use realistic or nonrealistic modes, separately or in

combination, as appropriate to the play. But this has only become clear

in the last fifty years, the postmodern era. In the period of our study,

1890 to 1950, the last half was

largely characterized by a reaction against realism, with the fifties and

sixties capping it off with the aggressively antirealistic

Theater of the Absurd. And so we come full circle.

Myron

Matlaw, in his Modern World Drama: An Encyclopedia, defines realism

thus:

REALISM

is as loose a term in the drama as it is in the other arts. It refers to

any attempt at reproducing verisimilitude on the stage. Since this could mean

the representation of external or internal, physical or psychological or

philosophical—or even political, sociological, or economic—-”realities,” and

since these may be perceived in many different ways, the term is almost

meaningless. Instead of being a description

of anything, it is popularly used as an evaluation,

usually an approving value judgment on the “truthfulness” of a work.3

“The term is almost meaningless,” says Matlaw. How dismayed Archer and some of the New Dramatists

would be to hear that this is the outcome of their struggle to force the drama

to be realistic. Yet Matlaw, in throwing up the

lexicographer’s arms at the futility of defining so slippery a word, is simply

being true to the spirit of his own postmodern age, an age in which not only

are the wisest scientists considerably less positive, not to mention less

positivistic, about reality than they used to be, but also we have considerably

less confidence about language’s relation to any reality outside itself.

From this skeptical postmodern perspective, then, latitudinarianism seems the

most becoming position to take. In any age it is difficult to empathize with

the heated arguments of the past if they are no longer of concern, but our

postmodern perspective makes it all the more difficult to cast ourselves back

to the 1890s and feel how burning the issue of realism was to the New

Dramatists (even as we grow cooler to the passionate arguments of Ionesco et

al. against realism). It seemed then

a life-and-death issue, at least for the drama.

The tone of William Archer’s plea for

realism in The Old Drama and the New is very telling. He obviously felt

beleaguered by those (such as Yeats) who would dismiss modern realistic drama

as inferior or degenerate. Archer’s object was to discover in the history of

drama a “guiding principle of evolution,” something that would help determine

“the essence of drama,” and that would provide “the basis for a rational

standard of values” by which the drama could be judged.4

Archer begins with the

assertion that the two sources from which drama arose were imitation (mimesis)

and passion. By “passion” he signifies “the exaggerated, intensified—in

brief, the lyrical or rhetorical— expression of feeling.”5 He cites song,

dance, and heightened speech as examples, but eventually includes almost any

stage business that he considers not exactly imitative of reality.

Imitation is the essence of drama, and all the lyrical-rhetorical exaggerative

elements, which he associates with “the primitive,” are impurities that need to

be purged from drama and delivered to the music hail, the opera, and the ballet,

the proper homes for the hysterical arts. The form that best accomplishes this

purgation is modern realism, imitation triumphant. “Who can doubt that the

future belongs to it?”6

With such notions, Archer’s history of English drama could only be mostly a catalog of failure, for that drama—with its speeches in verse, its asides and soliloquies, its direct address to the audience, its moralizings, its raked stages, its acting outside the stage-picture on apron or thrust, its indulgence in wit and rhetorical flourish, its formulaic characterizations, its boys disguised as females, its grand style of acting—was seldom realistic in the way he wanted.

Of

course Archer has to qualify every condemnation of the passionate

lyrical-rhetorical drama with the exception of Shakespeare. “Consummate genius

can express itself in any form and can ennoble any form.”7 One might draw the opposite conclusion that

Shakespeare succeeded, not in spite of his “passionate” form, but because of

it, but Archer’s idealism is proof against any such argument.

Surprisingly, toward the end of his book Archer offers Ibsen, heretofore the

model for the rule of realism, as another exception to the rule. “What he really

did was, not to confine his genius within the limits of realism, but to show

that realism of externals—of environment, costume, manners and speech—placed no

limits upon the power of genius to search the depths of the human heart, and to

extract from common life the poetry that lurks in it.”8 In other words, what made Ibsen great

was not his realism but his ability to get at the poetry (i.e., the passion)

beneath it. (Thomas Postlewait, in his Prophet of the New Drama: William Archer and

the Ibsen Campaign, has explained that this seeming contradiction

was based in Archer’s split personality. Archer was often very

appreciative of individual plays of the passionate-rhetorical type, including

some of Shaw’s, but for the sake of the theoretical consistency of his Ibsen

campaign he consigned such plays to a species more primitive than the New

Drama, thus repressing a part of his own appreciative nature and creating the

false impression that he was a fanatic.)

Archer

also refused to acknowledge that that which excepts

Shakespeare and Ibsen excepts Shaw. The concluding chapters of Archer’s

book are devoted mostly to encomiums of what we would now consider minor

playwrights—Arthur Wing Pinero, Sydney Grundy, Henry Arthur Jones, Harley

Granville Barker, James Galsworthy, etc.-—at the expense of a just estimate of

the period’s one giant, G. B. Shaw. In

an irony fitting of the New Drama itself, Shaw as the playwright who best

embodied Archer’s prophecy of a New Drama got little credit from the prophet

himself because he embodied it in a way that Archer could not theoretically

approve. But, then, Archer began as Shaw’s friend, neighbor, and rival

drama critic, and it must have been a struggle just holding his own against the

irrepressible Shaw. One wonders if

Archer’s constant reference to realism as “sober,” with its implication

that passionate drama was “drunken,” might not have been a sly joke at the

expense of the teetotaling but rhetorically

passionate Shaw.

At

any rate, Archer ends by congratulating imitation and lyrical-rhetorical

passion on at last consummating their divorce. “This divorce, so obviously

inevitable, is a good and not a bad thing—a sign of health and not of

degeneracy.”9 This could only have been written in

the early twenties, for the triumph of realism that Archer here celebrates was

soon to turn into the gradual rout of realism. Nothing could dramatize the

issue more clearly than the fact that in the year The Old Drama and the New

was published, 1923, Shaw produced his Nobel Prize-winning play, Saint

]oan, as passionate, lyrical-rhetorical,

and nonrealistic a play as he had yet written. It was a harbinger of the turn

he was to take in his last phase toward open “extravaganza,” one of Archer’s

most despised forms; and of the turn other dramatists, following continental

trends (Strindberg, Maeterlinck, Pirandello, Lorca, Cocteau, Anouilh, Brecht)

and American trends (O’Neill, Rice, Wilder, Williams), were to take toward

nonrealistic drama in general. The final twenty-five years of our period

saw realistic plays, looking increasingly stodgy, balanced off with a variety

of fresh-looking nonrealistic plays, the most interesting perhaps being the

Balinese-No inspired heroic drama of W. B. Yeats, the expressionistic

experiments of Sean O’Casey, and the revival of verse drama in the hands of

Christopher Fry, T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden, and Christopher Isherwood. And then

in the fifties the top blew off, with Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter providing

the antirealistic dynamite. Yet, though by the end of

our period pure realism seemed an exhausted form, imitation was soon to refresh

itself by connecting with a new sort of social protest (John Osborne’s Look

Back in Anger) and by combining in hybrid forms (Peter Nichols’s Joe

Egg), the moral seeming to be, the opposite of the one Archer drew,

that imitation and passion are elements within drama seeking, not exclusion of

the other, but a proper, dynamic relationship. The model for the future was Brechtian “epic theater” and Yeatsian

“total theater,” in which audience involvement in realistic and semirealistic episodes, and audience “alienation” through

nonrealistic dance, mime, ritual action, etc., alternated or combined in an

all-inclusive art.

Archer’s

polemic necessarily overstated the triumph of realism in his day; it was more a

temporary redressing of an imbalance created by the nineteenth-century’s inept

overindulgence in passionate, nonrealistic theater. Archer’s dedication to

realism was partly due to his sitting through too much frivolous song and dance

as a youth. But musicality was a peculiarity of nineteenth-century drama

caused by the historical accident that licensing laws dating from the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries prohibited straight drama from being

performed in all but three major theaters (Covent Garden, Drury Lane, and, in

summers, the Haymarket), making it necessary for the “minor” theaters to adorn

their dramas with music during, before, and after the play. These laws were

repealed in 1843, making straight drama possible for all theaters, but the

habit of musical accompaniment to drama persisted because it suited popular tastes, and so

melodrama still announced the arrival of the villain with a thrilling piano,

driving the young Archer to long for someone to shoot the piano player. Or at

least drive him out of the “legitimate” theater into the music hall and the

opera hall. If Archer had only noticed that his beloved Ibsen, in A

Doll House, had merely put the piano player onstage, to accompany

Nora’s tarantella, he might not have labored so diligently to separate

imitation from passion.

John

Russell Taylor sums up our present attitude. “In drama what seems natural is

natural—there are no legitimate or illegitimate illusions, only illusion

achieved or not achieved.10 Ironically,

our present liberation from the need to promote one kind of drama over another

has actually been to the benefit of the realists. As Shaw had pointed out in

the thirties, Ibsen’s psychological dramas would be served just as well by

acting outside the proscenium, in styles emphasizing their symbolism and

expressionism; nowadays one is just as likely to see Ibsen’s plays done in

theater-in-the-round or on a thrust stage, which gives them a whole new life.

Our freedom from dispute on these matters also allows us to appreciate

old-fashioned realism, realism acted behind the proscenium in a box set,

without any sense that that was ever an embattled form. Nowadays we care only

that the theater artists do their jobs—that is, create effective theater—and

how they do it is their business. Variety is the spice.

|

THE WELL-MADE PLAY AND THE PROBLEM PLAY |

Realism

was undoubtedly the dominant trait of Archer’s New Drama, but it had two other

features as well, deriving from the development of two separate kinds of

nineteenth-century drama—the “well-made play” and the “problem play.” Archer

often spoke of realistic drama as though it automatically included the salient

features of these two kinds of play, which were its “technique” and its

“subject matter.” Archer began by saying that “the advance of dramatic

art has consisted, not merely in the negative process of casting out extraneous

and illogical elements, but also in the positive process of acquiring a

technique appropriate to the great end in view—that, namely, of interesting

theatrical audiences by the sober and accurate imitation of life.” He

spoke of how French playwrights of the nineteenth century had “discovered the

central secret of modern technique—the infinite ductility or malleability of

dramatic material. In other words, systematic ingenuity had, almost for the

first time, been applied to the ordering of plot. The art of keeping action

always moving, and freeing it from the frippery of irrelevant wit and the

adipose tissue of wordy rhetoric, had been invented and developed.”12

Though Archer had gotten used to thinking of a certain plot

construction as endemic to realism, realism and the plot construction of the

well-made play actually came from different directions and were not mutually

necessary. Given credit for fathering the well-made play (or pièce

bien faite) was Eugène Scribe (1791-1861), fertile father of about

five-hundred plays. Mass production of plays on that scale requires machinery,

and it was Scribe who, so to speak, industrialized playwriting by creating a

plot machine for keeping an audience constantly intrigued. As John Russell Taylor

puts it, Scribe “saw that all drama, in performance, is an experience in time,

and that therefore the first essential is to keep one’s audience attentive from

one minute to the next. . . . His plays inculcated, not

the overall construction of a drama . . . , but at least the

spacing and preparation of effects so that an audience should be kept expectant

from beginning to end.”13 Telling

a story well, “so that there is not one moment in the whole evening when the

audience is not in a state of eager expectation, waiting for something to

happen, for some secret to be uncovered, some identity revealed, some

inevitable confrontation actually to occur,” is Scribe’s simple secret (so

ironically exploited by Beckett’s minimalist, plotless

Waiting

for Godot).14 It was left to Victorien

Sardou (1831-1908) to convert

Scribe’s machine for generating intrigue into a formulaic plot to give the

well-made play its reputation for tight construction. Sardou’s plot came

in parts—first, a quick exposition, introducing characters and filling in their

pasts, followed by an inciting event (a misunderstanding, a secret withheld, an

intercepted message, a visit from a mysterious stranger, etc.) that causes the

action to rise in tension, act by act in incremental steps, toward a scène à faire, a climactic confrontation that forces the

action to a crisis and a denouement, a resolution of maximum sensation. And

there was to be no wasted motion, no “fripperies” of poetry or rhetoric such as

a Shakespeare or a Shaw would indulge in. Eugène

Labiche (1815-88) and Georges Feydeau

(1862-1921) adapted the

“well-made” formula to comedy, putting the emphasis on bigger and bigger laughs

instead of on bigger and bigger thrills. In the well-made play, pattern

is all. Character and theme are subordinated to plot

intrigue. Though “well-madeness” became

identified with realism, it was originally intended to apply to any

form—farce, melodrama, heroic tragedy, whatever. Chekhov’s plays,

especially, illustrate that “well-madeness” is not only not necessary to realism but may actually be

counter to the assumptions of realism, since life is seldom “well-made.”

Conjoining

with the well-made play in the New Drama was the "problem

play." Shakespeare’s dark comedies, such as Measure for Measure, have

been called problem plays, so the type has been around; but according to

Archer, it was Sydney Grundy who first used the term, disparagingly, after he

gave up writing such plays (Shaw would say it was because he wrote them

poorly!).

However,

it may have been the Danish critic, George Brandes,

early celebrator of Ibsen’s genius, who in 1872 broached the idea of the

problem play. Wrote Brandes,

“What is alive in modern literature shows in its capacity to submit problems to

debate.”15 Supposedly,

Ibsen later embodied this best in the discussion between Nora and Torvald at the end of A Doll House concerning modern

middle-class marriage. Such debate connected with realism in that it

provided a way for drama to come to grips with “real life” by dealing

straightforwardly with social problems. But Ibsen was misunderstood. To

paraphrase a critic, to say that A Doll House is about women’s

liberation or that Ghosts is about venereal disease

or that An Enemy of the People is about political corruption is like

saying that “King

Lear is about housing for the elderly.”16 Those who misunderstood Ibsen wrote

plays about slum landlordism, prostitution, labor unrest, penal codes, class

warfare, the double standard, divorce, business corruption, etc., in such a

very limited and narrow way that they gave the problem play a bad name.

The reason even a Sydney Grundy might speak disparagingly about problem plays

is that such mundane matters—when dealt with at only a literal, local, topical

level rather than at a level that questions human identity and destiny, as in

Ibsen and Shaw—could easily degenerate into political tracts or propaganda

pieces. Problem plays became identified with thesis plays, didactically

presenting social problems for the sake of promoting a particular reform or

upholding convention. A favorite “problem” of New Dramatists such as

Jones and Pinero was the issue of whether a “fallen woman” could be allowed

back into respectable society, and the answer was always “no.” It’s ironic that

the sort of play Archer championed for its subtle, objective presentation of

reality was so often secretly moralizing, imposing ideals or ideology on

reality rather than “telling it like it is.”

SHAVIAN NEW DRAMA

|

TOP / Table

of Contents

The

ending that allowed no happy solution to the fallen woman question was problematic

when compared with the sudden and miraculous reconciliations, conversions, and

other providential workings that marked the hasty denouements of melodrama, yet

Shaw was quick to point out that problem plays of the Pinero and Jones variety

were phony, for the conclusions were foregone, their unhappy endings not really

following from character and event but merely mechanically imposed by moral

conventions, ideology, external to the play. In The Quintessence of lbsenism (1891), Shaw argued that Ibsen, on the

other hand, in implying that the quintessence of morality was that there is no

quintessence, that there are no easy or final solutions to the problems life

poses, had meant that the conventional ending was part of the problematics—that

is, if a play’s ending, simply as a matter of convention, automatically says no

to the question of whether a fallen woman can get back into society, that

ending should not resolve the issue, as Pinero and Jones would let it seem

to do; rather, it should expose an irreconcilable conflict between the

individual will and the conditions that seek to govern it. Understanding

Ibsen in this way, Shaw made “problem” the center of his own program for the

New Drama. “Problem” simply needed to be understood correctly. “Drama,” said Shaw, “is the presentation in parable of the conflict

between man’s will and his environment—in a word, of problem.”17 Shaw thought the dramatist should deal

with social issues, but only as the context for a dramatization of the larger,

universal conflict between private will and circumstance, showing the

individual struggle to realize an identity and a purpose in a mysterious

universe. Such problems are timeless, however localized by their time and

setting.

With

the well-made play, however, Shaw was not interested in saving a misunderstood

form—he attacked it wholesale. Well-made plays were merely “mechanical rabbits”

leading the audience like dogs on a merry chase, but to no lasting or

significant purpose. Shaw believed that

plays should grow organically, from character and situation, rather than have a

ready-made plot imposed on them. It was greater realism, he argued, to

let life go where it would rather than force it into an artificial, prejudging mold. Further, in The Quintessence of Ibsenism he declared that the discussion in

dramatic form of a “problem” was the technical novelty in Ibsen’s plays that

should replace the old Scribean art of

intrigue. For intrigue “Ibsen substituted a terrible art of sharpshooting

at the audience” through a discussion technique that implicates the audience.18 And if discussion is allowed to follow

naturally from character, then the play, like life, will not be

“well-made.” The well-made play of “Sardoodledum”

(referring to Sardou) was a falsifying apparatus that Shaw saw as contradicting

all the assumptions of that realism to which it was allied.

Yet

Shaw was not interested in defending dramatic realism either. “Stage realism is

a contradiction in terms,” he said.19

It was not Ibsen’s literary realism that made him great but his

psychological, philosophical, and critical realism. The Ibsen Shaw

presents in The Quintessence of Ibsenism is a

visionary, much akin to Ibsen’s own view of himself. His surface realism

was subterfuge, a cover-up and symbolic signpost for the poetic divination that

was going on behind the scenes.

Believing

that great artists express themselves authentically, not by fitting into a

standard formula for art, but by having an individual style, Shaw saw the

appropriateness of Ibsen’s style, expressive of his secretive, subversive

character. In devising his own (acquired) style, that

of an open, flamboyant extrovert, devoted to frontal attack, Shaw felt

he must acknowledge stage illusion for what it was. “Neither have I ever

been what you call a . . . realist. I was always in

the classic tradition, recognizing that stage characters must be endowed by the

author with a conscious self-knowledge and power of expression, and .

. . a freedom from inhibitions, which in real life would make them

monsters of genius. It is the power to do this that differentiates me (or

Shakespeare) from a gramophone and a camera.”20 Furthermore, the object of drama

for him was “the expression of feeling by the arts of the actor, the poet, the

musician. Anything that makes this expression more vivid, whether it be

versification, or an orchestra, or a deliberately artificial delivery of the

lines, is so much to the good for me, even though it may destroy all the

verisimilitude of the scene.“ 21

Shaw’s

strategy was to make the realistic well-made problem play ridiculous by showing

its self-contradictions and its failures to live up to its own model. The

New Drama of this sort having been exposed as fraudulent, the stage would thus

have room for his own New Drama, sometimes called by him the “Drama of Ideas”

but a more complex thing than that label suggests, as we’ll see later. His

strategy succeeded admirably to the extent that it certainly made room for his

own plays and the plays of other dramatists uncomfortable with realism, but the

record is otherwise mixed. A look at the drama of the twentieth century

shows that Archer’s ideals seem to be more in practice than Shaw’s until about

1930 and that from then on there is a swing in Shaw’s direction, although in

any given London season one could find both sorts of plays.

So

which was the real New Drama—the realistic well-made problem play of

Archer’s theory or Shaw’s fabulous, passionate Drama of Ideas? Archer’s type no doubt was in the majority

(though, curiously, the few plays Archer wrote himself do not fit his own

theory). But as for quality and lasting value, Shaw’s type clearly

prevailed, if only because Shaw himself was the best playwright. It also

prevailed in the sense that there no longer seems any question of pure realism

being a superior art form or of there being any constraint on dramatists

wishing to write passionate drama. It may also have prevailed because, in

a contentious age, full of great battles between Victorian and modern ideas and

between rival theories of modernism, a rhetorically passionate drama of ideas

was a fitter vehicle for expressing the age.

THE STAGE AND THE AGE

|

TOP / Table of

Contents

Henrik Ibsen as a young man, looking at what seemed a

hopelessly corrupt and wrong-headed society, declared that a total revolution

was needed, one more thorough than the biblical flood, which left survivors. In

the next revolution, he said, we must “torpedo the ark.”22 A quick glance

at our period suggests that the 1890-1950 era came surprisingly close to effecting

complete revolution, even to the sinking of more than one ark. It’s

amazing how much historical incident and social and technological change was

crowded into this period. It was a time of both gradual and cataclysmic

transformations, unprecedented in amount. So much so that even Shaw, one

of the most ardent advocates of change, complained toward the end of his long

life of the dizzying rapidity of change and in many of his late plays presented

characters who were victims of what we would now call “future shock,” the

disease that comes from having the future come at one too fast.23

Shaw’s exaggerative

persona, the clownish G. B. S., like Ibsen’s “torpedo” metaphor, was a sign of

how desperate a measure was thought needed to overcome Victorian inertia in

social-moral-religious concerns; but the “dynamite” personality Shaw devised to

explode Victorian conventions resulted in more than he bargained for (though of

course he was not the only “dynamitard”). For a

period conceived of as glacial in its movement at its beginning found itself

more and more resembling an avalanche. There is some moral here for those who

would “start the ball rolling,” but of course the moral wouldn’t be necessary

if societies didn’t try to keep balls from rolling altogether.

A

simple contrast between beginning and end is eloquent enough. In 1890 the horse and buggy still ruled

the road; by 1950 automobiles had chased the few horses left to the country,

and airplanes made both look like they were standing still. In 1890

The

philosophical and scientific underpinning for this

social-political-technological change was the theory of evolution. Charles

Darwin in 1859 had given voice to the

inklings of a half century or more of scientific speculation on the origin of

species, and by the nineties his theory of evolution had won sufficient

acceptance. An alternative theory, that of Lamarck,

was preferred by some, but Lamarckian and Darwinian were united in their

understanding of life as evolving. With change being the law of life, and a

better or higher life apparently being the result of change, or at least

desired and aimed at,

some reasoned that the more change the better. Some thereby

deified Change and pursued it, in the form of novelty, for its own sake.

Soon people found themselves coping with “the tradition of the new,” in which

fad was required to replace fad at an ever-accelerating rate.24

Art

forms tended not to last long, for the modernist avant-garde was always moving

on. The theater, too, though as usual slower to change, eventually got caught

up in the same frenzy, as experimental theaters of the off-off-Broadway or

“fringe” sort, following the lead of Archer, Elizabeth Robins, and J. T. Grein in the nineties, began to attract a select patronage

and steal prestige from the established theaters of London’s West End.

Perhaps

the most remarkable of the experimenters in staging was Edward Gordon Craig

(1872-1966), son of the actress Ellen Terry. Reacting against the heavy

sets of a too literal-minded and literary-minded theater, he attempted to

create a sparer, more fluid, poetically suggestive, and psychologically attuned

style, which served well the aggressively antirealistic

and antiliterary theater of a later generation.

Craig’s revolution can also be understood as part of a general trend to replace

the old actor-manager—who along with being the star was responsible for all the

details of production—with a nonacting manager or

director and other specialists, such as the artistic designer.

The

most radical experimentation in the drama was found mostly in the “little

theaters” in the provinces (Liverpool, Manchester, Bristol, Cambridge,

Birmingham, Glasgow, etc.); in suburban London (the Lyric Theatre in

Hammersmith, the Everyman Theatre in Hampstead, the Royal Court Theatre in Sloane

Square, the Old Vic below the South Bank, etc.); in theater groups that moved

about and hired halls (the Independent Theatre of J. T. Grein, the New Century Theatre of Archer and Elizabeth

Robins, the Stage Society, etc.); or in Dublin’s Abbey Theatre. Their

continental progenitors were Ole Bull’s National Theatre in Norway in the

1850s, the Duke of Meiningen’s company in the Germany

of the 1870s and 1880s, Antoine’s Théâtre Libre in Paris from 1887, Otto Brahm’s

Freie Bühne theater in Berlin from 1889, and Stanislavsky’s Moscow Art

Theater from 1898.

Another

consequence of evolutionary theory that seriously affected the theater was the

rationalization of “social Darwinism,” used as a justification for a ruthless

free-trade economy that, following the law of the jungle, saw the strong get

stronger and the weak get eliminated. The doctrine of “survival of the

fittest,” which in business often meant the survival of the unscrupulous,

seemed to justify unfettering the competitive instincts from ethical

constraints. When certain men prided themselves on “being realistic,” they were

not referring to literary realism but to an acceptance of the desire for

aggrandizement as an honest basis for human society. This had a very sorry

effect on the theater, for, while the theater has usually been at the mercy of

the box office, the actor-managers, who still controlled most of the West End

theaters in 1890 and who, even at their worst, had some aesthetic sense and

some fellow feeling for the actors and artisans under their command, were

gradually replaced by businessmen, often in multiple-ownership syndicates, who,

having no feeling for the theater as a cultural institution with a special

heritage, treated the theaters they owned as they would any other piece of real

estate—no sentiment was allowed to mix with the cash flow. And, treating the

actors as the capitalist everywhere treated labor, they forced the Actors’

Association in 1919 to

reorganize as a trade union and theatrical agents to appear as middlemen.

Although the modern period saw as many theaters built as had the nineteenth

century, many of the new theaters were merely replacements for older theaters

that had been razed or converted to make way for more profitable ventures. Of course, capitalism’s Great War, inviting

bombardiers to compete for the most destructive “strikes,” made rubble of a few

theaters as well.

Newly

built West End theaters at first followed the trend toward realism by

building the sort of smaller, more intimate, fan-shaped picture-frame theaters

that T. W. Robertson and the Bancrofts had shown in

the 18ó0s to be the most suitable for the subtler, understated style of acting

required by realism. The older style of huge, deep, horseshoe-shaped theaters

with large aprons set by the patent houses of

The

new theaters may have been designed for a less showy, less histrionic sort of

play, but at the beginning of our period, the increasing wealth and social

prestige of their patrons made luxurious display, greater comfort, and

ceremonial opportunity features of theater construction. The backless benches

of the nineteenth-century pit were pushed farther and farther to the back and

replaced by plush, expensive seats called “stalls,” with the pit seats eventually

disappearing altogether. Proscenium arches were supported by groups of statuary

or gilded pillars; boxes were draped with colorful plush, their fronts

embellished by vases, medallions, frescoes, caryatids, and the like; and

gorgeous crystal chandeliers hung from decorated ceilings, adorned perhaps with

gold leaf. Foyers, saloons, smoking rooms, and buffets were found at the

front of the house, lavishly decorated in various historical styles. No

expense was spared backstage either in the use of stage machinery or any modern

technology that would make the show more impressive. As the period wore

on, however, the increasing democratization of the populace and the hardships

of wartime and economic depression toned things down considerably in the theater.

When “the talkies” came in, in the late twenties, some theaters were built in

cinema style, with straight lines replacing the curved auditorium, stage boxes

eliminated, and decoration reduced. Eventually virtue was found

even in the relative plainness of the “little theaters” of the suburbs and

provinces.

At

first the provincial theater lost ground to the London theater when, with the

increasing availability and affordability of the railroads and other

transportation, Britain’s far-flung population was able and eager to get to

London for a holiday. London-based national newspapers carrying the drama

reviews of Clement Scott, William Archer, A. B. Walkley,

Max Beerbohm, et al. were persuasive of the attractions of

While

one could still find theaters in the 1890s that offered the multiple fare that

had been standard throughout the century—consisting of opening play, main

piece, and closing play, with variety acts before, after, and in between,

lasting sometimes from 6:00 to after midnight—the majority of

theaters, catering to the advance of the dinner hour to 7:00 in polite society,

had gone to a single play offering, opening at 8:00 or thereabouts, and soon

this was universal. A wider adoption of the matinee further served the schedule

of a more leisured gentility and of a female populace more inclined to venture

out.

Following

the lead of T. W. Robertson and the Bancrofts, the

theater of our period begins by being obsessed with respectability. Theater

people wanted the theater to be thought a proper place for ladies and

gentlemen, on both sides of the footlights. Fighting to free the theater of the

ruffian clement that had lowered the tastes of its audience throughout the

century and of the bohemian element that had caused its actors to be suspected

of vagabondage, many theater people craved above all else social acceptance, some

as much for the elevation of their art as for themselves. Success came when the

leading actor of the day, Henry Irving, was in 1895 the first actor to be

knighted, soon followed by Squire Bancroft in 1897. Then began the great push

for a similar acceptance for dramatists, led by Henry Arthur Jones’s campaign

of probity, but not consummated until W. S. Gilbert was knighted in 1907 and Arthur Wing Pinero in 1909. But far more knighthoods

went to actors than to dramatists over the years. Shaw eventually turned one down.

English-style

realism was timely to the actor’s quest for respectability. Though continental

and American realism often descended into the lower depths of the factory workers

and peasantry with unpleasant depictions, English realism, at first anyway,

tended to focus on the upper middle class and aristocracy. To look at the stage

of a realistic English “society drama” was to see the

latest smart fashions in interior decorating, clothing, hair styling, manners,

and small talk. And as the acting of such a piece called for the sort of

behavior one would encounter in the day’s drawing rooms, the actors,

cup-and-saucer in hand, could, with properly clipped accents, downplay and

understate in the best tradition of the reserved British gentleman. Such

understatement can be made theatrical, but often it wasn’t. To those brought

up on the grand style of acting so prevalent during the century, as Archer had

been, however, the realistic cup-and-saucer school of acting seemed refreshing.

But

all things pale, and among the first to feel the paling of this relatively untheatrical theater was Shaw, who as drama critic for the Saturday

Review from 1895 to 1898 soon grew weary of staring into

drawing rooms watching insignificant people do and say insignificant things in

an insignificant way, compounding their insignificance by pretending they

weren’t actors on a stage engaged in an important ritual. For Shaw, the

fashion show the actors provided was no compensation (though the pretty

actresses almost sufficed). For him such plays were basically “a tailor’s

advertisement making sentimental remarks to a milliner’s advertisement in the

middle of an upholsterer’s and decorator’s advertisement.”25 The fashionable, polite, well-bred,

well-made, realistic drawing-room drama of the day, though winning

respectability for actors and dramatists, Shaw perceived as simply watered-down

melodrama, and he preferred his melodrama straight.

And

so, with Shaw’s opposition, which was buttressed by the staging experiments of

Gordon Craig, by the heroic acting style required by William Butler Yeats’s

mythic drama and Gilbert Murray’s Greek revivals, by the Irish “soul music” of

Synge and O’Casey, and of course by continental influences, no sooner was the

realistic school of acting

established than reaction against it set in. The history of the struggle

follows that of the drama, first a seeming triumph for realistic acting, then a

gradual retreat from it, moving toward a gradual acceptance of the view that a

well-trained actor had better be schooled in both methods if he is to be fit to

play the entire repertoire. Not the least of the successes of this period

was the establishment of several schools of acting where initiates could learn

their trade, with Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (1904) the most important (which Shaw

acknowledged by helping to fund it). Yet what they learned at such schools,

such as the teamwork of ensemble acting, was not always germane to the way

things were.

The

theater seems always plagued and blessed by the need for star actors. Blessed because the star system gives the

most opportunity to the best actors to display their art (the age would have

been much the poorer if such names as Henry Irving, Ellen Terry, Florence Farr,

Herbert Beerbohm Tree, George Alexander, Charles Wyndham, Mrs. Pat Campbell,

Johnston Forbes-Robertson, Gerald Du Maurier,

Gertrude Lawrence, Sybil Thorndike, Ralph Richardson, Cedric Hardwicke,

Beatrice Lillie, Paul Scofield, John Gielgud,

Laurence Olivier, and Edith Evans, had not graced its playbills, billboards,

and marquees), plagued because the system exaggerates the importance of the

star actor at the expense of the play and of the acting ensemble. Our period is

no different in this tension. The dramatist’s drive throughout this period was

to restore literary worth to playwriting, and his enemy was always the star

actor who would sacrifice the written play to the display of a personal style.

That had precisely been the bane of nineteenth-century theater,

from the writer’s point of view. In

modern times only Noel Coward, star of his own plays, had it both ways. Perhaps the happiest of the nonacting playwrights were ones, like Shaw, who wrote

in plenty of personality and theatricality and who had made peace

with the popular theater by employing all its “biz” and “shtick” in the

interests of a higher drama. Yet even

Shaw was shut out of the commercial theaters for many years.

The struggle between the requirements of the higher drama for

disciplined ensemble acting and the commercial theater’s need for stars was

only one aspect of the war between quality and quantity that marked the age.

The only resolution to the dilemma of the higher drama’s inability to attract

audiences in sufficient quantities was an endowed national theater. The need

for such a theater had been noted for a long time, but as far as the New Drama

was concerned, an 1879 visit to

FIGURES

|

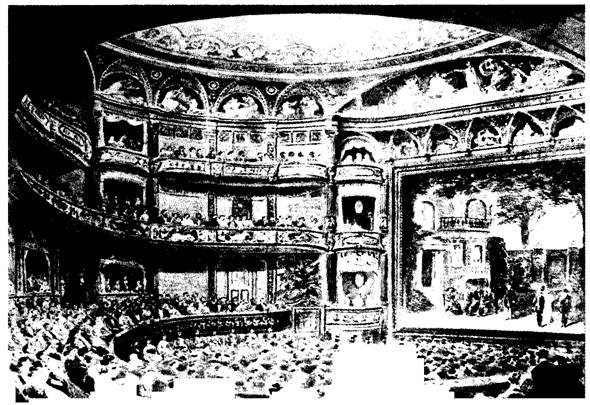

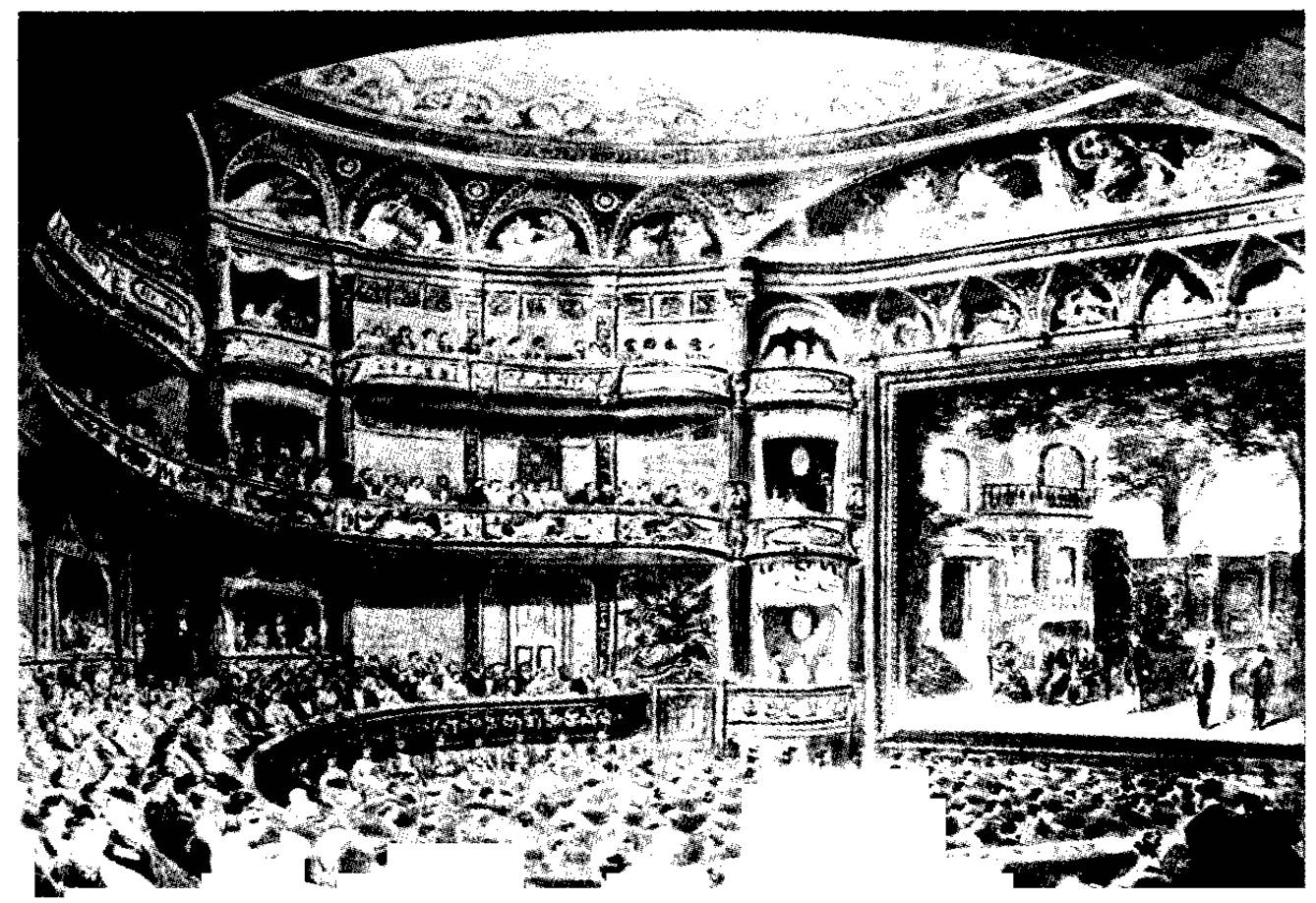

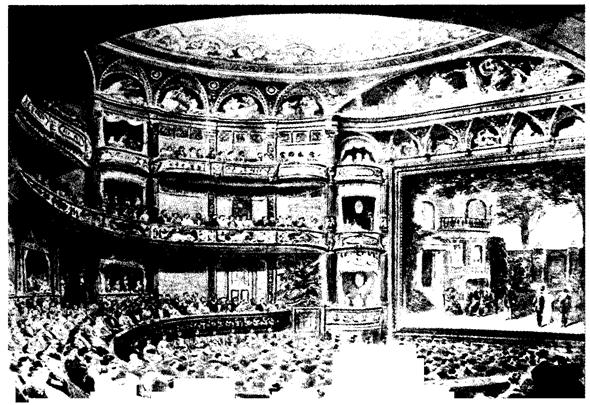

Figure 1 (below) – The Haymarket Theatre, 1880; Bancroft’s

picture-frame stage.

Courtesy of the Raymond Mander and Joe Mitchenson Theatre

Collection Ltd.

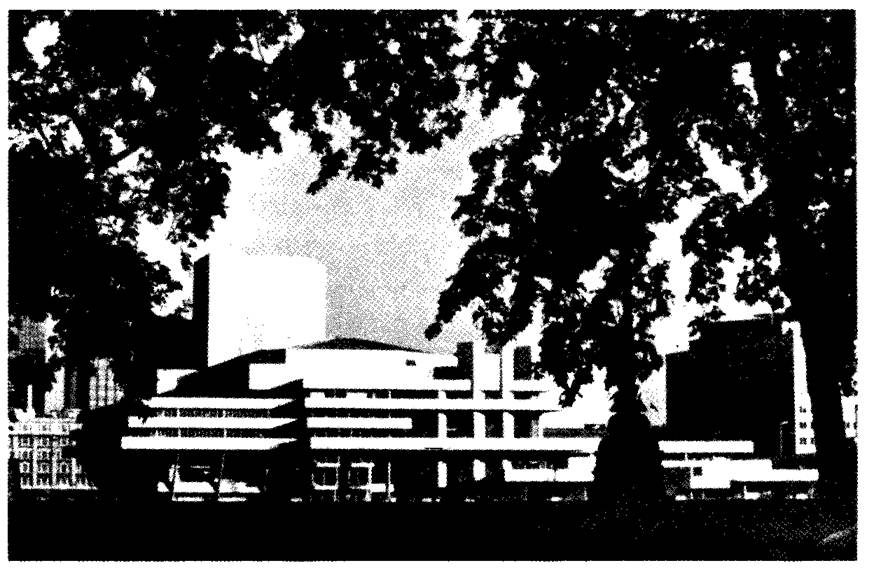

Figure 2 (below)---The

National Theatre on London's South Bank, opened in 1967.

Figure

3 (below)---Oscar Wilde, a less than ideal New

Dramatist.

Photo: Eliis and Walery,

Figure 4 (below)---Aubrey Beardsley's drawing

of

a climactic scene from Wilde's Salomé

|

|

Figure 5 (below)---The diabolical Shaw.

Figure 6 (below)---Punch

cartoon portraying Shaw as Pan

(like

Dionysius, a goat-footed deity representing the primacy of Nature),

which

could stand for Shaw's attempt to lure the drama back to

its

Greek origins as life-worship. Courtesy of Punch

Figure 7(below)--Design for a statue of "John Bull's

Other Playwright:

After Certain Hints by 'G.B.S.'" Punch cartoon by E. T. Reed

Link to Chapter

2: “‘Our Theatres in the Nineties’: Haunted by Ghosts”